A Phil Hall Op-Ed: Pop culture aficionados recognize Hattie McDaniel as a performer with a history of breaking entertainment barriers. She was the first Black woman to sing on radio, the first Black performer to win an Academy Award with her performance in “Gone with the Wind,” and the first Black entertainer to star in a national radio series with the popular comedy “Beulah.” But housing industry professionals should also be aware of another accomplishment by this gifted star – 80 years ago this week, she led an effort that resulted in one of the first major breakthroughs in the fight against housing discrimination.

In 1942, McDaniel moved into West Adams Heights, a Los Angeles neighborhood that saw Black entertainers and business leaders among its residents. Among McDaniel’s most notable neighbors were the entertainers Louise Beavers, Ethel Waters, and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, insurance industry executive Norman Houston, and dentists and civil rights activists John and Vada Sommerville. The area was nicknamed “Sugar Hill” after the section of New York City’s Harlem that was home to many prominent Black celebrities and professionals.

Despite her fame and prominence, eight white residents in West Adams Heights were unhappy with her arrival and with the growing presence of Black neighbors. They dug up paperwork from the 1902 development of West Adams Heights and highlighted a restrictive covenant that barred “non-Caucasians” from owning property in that community. Their attempts to voluntarily enforce the covenant failed, and by 1945 they decided to file a lawsuit against 50 Black households in the community, claiming that “that if restrictive covenants were not enforced, their property would lose value and racial clashes would inevitably ensue.” McDaniel was among those being sued, marking the first time that an Oscar winner was accused of bringing down property values.

Of course, 1945 saw the end of World War II and a new push for civil rights by Black Americans who joined the military and fought for freedom overseas but were treated as second-class citizens in their own country. McDaniel was no stranger to racism – she was barred from attending the “Gone with the Wind” premiere in Jim Crow-era Atlanta – and she was not going to kowtow to her intolerant neighbors.

McDaniel hosted workshops at her home to plan the strategy for fighting the case in court. This was not going to be an easy case, since the courts of that era rarely favored Black Americans in their pursuit of social justice. However, McDaniel possessed expert planning abilities – she served as chairman of the Negro Division of the Hollywood Victory Committee during World War II – and she built up a brigade of 250 supporters who joined her in Los Angeles Superior Court on Dec. 5, 1945, to fight for the rights of the neighborhood’s Black residents.

In the opening arguments of the case, the attorneys representing the white plaintiffs claimed the Black residents of West Adams Heights had to give up their homes because they were in violation of the restrictive covenants. However, Loren Miller, a prominent Black attorney representing the defendants, stated the covenants violated both California’s state constitution and the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution.

Judge Thurmond Clarke heard the arguments and took it upon himself to visit the neighborhood in question. The following day he dismissed the case, siding with Miller’s defense argument.

“It is time that members of the Negro race are accorded, without reservations and evasions, the full rights guaranteed them under the 14th amendment of the Federal Constitution,” Clarke ruled. “Judges have been avoiding the real issue too long. Certainly there was no discrimination against the Negro race when it came to calling upon its members to die on the battlefields in defense of this country in the war just ended.”

Clarke’s ruling created a political shock in its denunciation of housing discrimination – the 14th Amendment was never previously cited by a judge in a case of this nature. The plaintiffs appealed, but their case languished in the court system and ultimately became moot when Miller joined with Thurgood Marshall in successfully arguing the 1948 Shelly v. Kramer case before the US Supreme Court that declared racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable. Sadly, many developers and local governments would ignore that ruling, and two decades would pass before the Fair Housing Act of 1968 codified the prohibition against such covenants.

McDaniel responded to Clarke’s ruling by stating, “Words cannot express my appreciation,” adding that Clark was “a fine judge.” But it was McDaniel’s refusal to be forced from her home that laid the foundation in the fight to ensure discrimination has no place in the pursuit of the American Dream of homeownership. Arguably, that triumph surpassed any show business accolade she ever earned.

Phil Hall is editor of Weekly Real Estate News. He can be reached at [email protected].

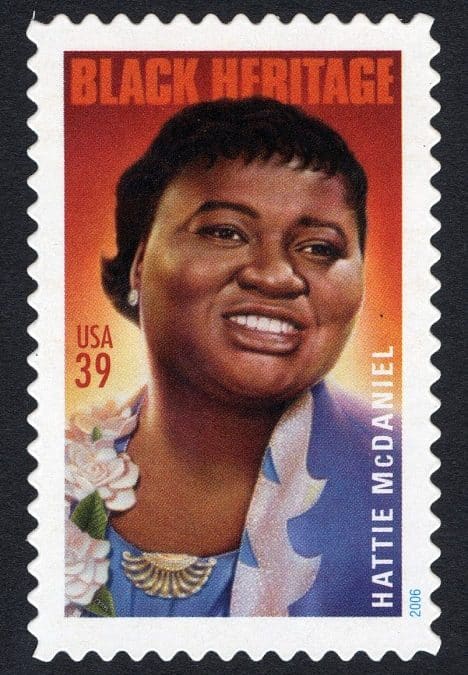

Photo courtesy US Postal Service / National Postal Museum

Great piece of history Phil! Thanks for this Op-Ed. It qualifies as a top story for the week, month or even year! Back in 1986 I bought a vacant lot in a plated early 1960’s subdivision of custom homes in the suburbs of NE Indianapolis. I was just 5 years into my 42 year Real estate career. When I got the title work from the Listing agent’s title company I was shocked that deep in the covenants was a statement that prohibited any persons of color to buy a lot or home in this subdivision. I was shocked that these kind of statements still existed. I knew that they couldn’t be enforceable. I spoke with the Board of Realtor’s legal representative on retainer and they too assured me the discriminatory statement was null and void and totally unenforceable. We’ve all had dozens of discriminatory classes and courses in brokerage and appraising but I was seeing an actual part of past history right before my eyes! Martin Luther King famously said in that civil rights rally in outdoors Washington DC that he had a dream that someday his children would be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I’m glad that Hattie McDaniel lived to see her lawsuit prevail and hopefully she lived in that neighborhood as long as she wanted. I wish Martin Luther King could have lived to see the fruition of the massive housing civil rights changes that followed from much of his work. I love America in so many ways with housing civil rights right up near the top.

Great article! Thank you! As a Los Angeles Broker, it hits home. Thank goodness these type of covenants are no longer enforceable!