Angelo Mozilo, the former chairman and chief executive of Countrywide Financial who received widespread criticism for his role in the subprime mortgage meltdown, died at the age of 84.

“It is with great sadness that the family of Angelo Robert Mozilo announces his passing from natural causes,” said a statement from the Mozilo Family Foundation, a philanthropy that he founded. “The family requests privacy at this time.”

Mozilo was born in 1938, in the Bronx, New York, the eldest of five children. His father ran a butcher shop where he worked during his teen years, but his mother was opposed to having him follow in his father’s footsteps. He attended Fordham University, primarily because its Bronx campus was close to his family’s home, thus enabling him to save money that would have gone into dormitory expenses.

Mozilo graduated in 1960 and became a loan officer with a mortgage company. That company was merged with another owned by David S. Loeb, who viewed Mozilo as a protégé and encouraged him to develop new business opportunities. In 1969, Loeb hired Mozilo as his second-in-command for a new venture called Countrywide Credit Industries. The company was originally based in New York City, but later relocated to Pasadena, California, when Los Angeles underwent a housing expansion.

Countrywide was unusual at the time, being a nonbank mortgage lender in an industry dominated by banks and thrifts. The company stayed competitive by being an early adopter of automated technologies, and through the early 1980s it became favored with wealthy customers who needed jumbo loans to finance luxury property purchases. By 1985, Loeb and Mozilo launched Countrywide Mortgage Investment as a vehicle to collateralize these loans for sale to private market investors. Countrywide Mortgage Investment would become IndyMac Bank, which was realigned as a standalone company in 1997.

One area where Loeb and Mozilo had different opinions regarded subprime mortgages – Mozilo was eager to plumb that market but Loeb was concerned about their risk. Loeb eventually compromised by creating a subsidiary called Full Spectrum Lending in 1996 to focus exclusively on subprime, but after Loeb’s retirement in Mozilo went full-throttle into the subprime market. Although Mozilo’s interest in subprime was initially admirable – he felt the product could help bridge the disparity gap between White and Black homeownership rates – he was also concerned about losing market share to other active participants in that sector.

At first, Mozilo’s risk paid off – Fortune magazine highlighted Countrywide as the “23,000% stock” because it provided investors a 23,000% return between 1982 and 2003. Mozilo also became prominent on Wall Street and in Washington, creating a secret VIP program for mortgage lending that catered to the corporate and political elite.

However, Countrywide’s pursuit of loan quantity came at the sacrifice of loan quality, with sloppy underwriting on mortgages originated for many customers who should not have been approved for funds. By 2007, Countrywide’s reputation evaporated to the point that no major bank would finance its short-term debt – Mozilo managed to stitch together $11.5 billion from pre-established lines of credit via a network of 40 banks.

Bank of America Corp. acquired Countrywide in January 2008 for $4 billion dollars in stock. While Mozilo was out of the C-suite, he was not out of the spotlight – during 2008, news of a “Friends of Angelo” list emerged regarding Mozilo’s too-cozy relationship with Washington power brokers including Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd, Housing and Urban Development Secretary Alphonso Jackson and Paul Pelosi Jr., son of Rep. Nancy Pelosi.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filed securities fraud charges against Mozilo in 2009, claiming he misled investors on the soundness of the company and charging him selling his Countrywide stock based on non-public information that generated a $140 million profit ahead of Countrywide’s collapse and sale to Bank of America. He reached a $67.5 million settlement with the SEC that included a lifetime ban from serving as an officer or director of a public company.

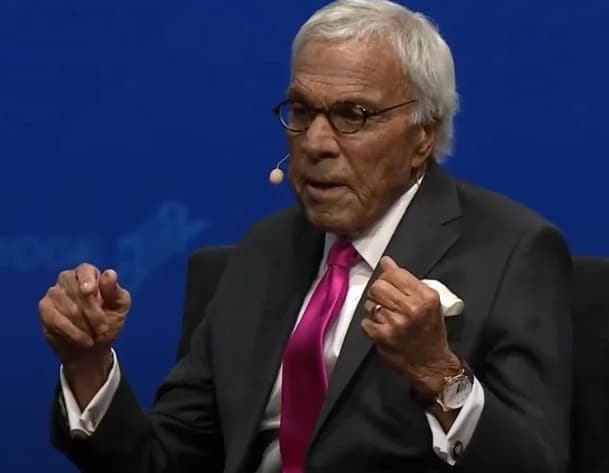

Time magazine would place Mozilo at the top of its list of the 25 People to Blame for the Financial Crisis, but he made little attempt to salvage his reputation. Mozilo mostly disappeared from public view after the SEC settlement and lived out his retirement years in a mansion in Santa Barbara, California. In May 2019, Mozilo made a rare guest appearance at SALT Las Vegas, a hedge fund conference, where he offered no responsibility for his role in the subprime meltdown.

“Somehow, for some unknown reason, I got blamed for it,” he said. “A lot of years went by. My wife passed away, I turned 80 years old, and now I don’t care. There’s other things more important in life.”

Photo: Screenshot of Angelo Mozilo at the 2019 SALT Las Vegas conference, courtesy of SALT’s YouTube page.

Angelo lived to see paper-less mortgage loan products. He succeeded. He did more things right than wrong and I’m still a supporter of his ingenuity and passion for the business.

He was a criminal. Pure and simple.

This is the first article I have read about Angelo that is fair and factual. I worked at Countrywide when they first dipped their toes in the subprime market. I also got my Wife a job there as a SubPrime Account Executive. The truth is that CW was one of the last lenders to get involved. They were by no means the face of SubPrime paper. I also know quite a bit about Angelo as he started in the mortage industry’ at my Grandfathers mortgae company and title company in Brooklyn. He should not be remembered as the face the of the 2008 collapse at all. They just had to put a name to it, and blame. His company was huge, so he was an easy target. He was no angel, but he was also not what many claimed him to be. At least you did some real fact checking on this, and for that I applaud you!

Easy target….please…..they wrote so many bad loans and tried to pawn them off as A+ to investors. You have no idea what you are talking about.

Conning others to buy high risk loans without disclosure was and still today remains today, a criminal offense. This man skipped out of jail time because of his high level connections. Crime pays for some.